Adlah Alkurdi is GPG’s Head of Policy. She has over 10 years of experience in managing the design and delivery of political strengthening and public sector reform programmes, resulting in the establishment of new legislation, policies, and procedures. She has been thoroughly involved in our work across the MENA region and in complex and fast-evolving political context. In this blog, she reflects on her experience and learnings from working in those environments.

Almost ten years ago, I found myself working – or in other words, my passion led me to work – in contexts where development assistance is crucially needed but incompletely delivered. I spent a few years working in one of the most marvellous countries in the world, yet also one of the most fragile and conflict-ridden: Libya. In early 2013, that gem of a country, with its immaculate shores by the Mediterranean, had strong prospects for building a state with its thriving civil society and its young population who were eager to disarm and join forces with politicians to build their country. A country of transparent institutions, of strong rule of law, and accountable governance, something Libyans had not experienced for over 40 years of Gaddafi’s rule. But reality painted a different picture, and a different future. Divisions and conflicts over which political group should lead and monopolise power and control, alongside the state of chaos and frenzy of the post-liberation period, was a recipe for disaster for Libya. Political leaders failed to agree and unite on what would serve all Libyans, and too many gave in to corruption. What struck me the most was some politicians’ apparent poor understanding of the grave impact of their inaction and indecisiveness, a motif I have often observed in my work across international politics.

My experience is that political, high-level decision-making capacity is often extremely limited, as this power has always been the privilege of the select few. The culture is to implement without questioning and to take things at face value – this is taught at a young age, in schools, at homes: to follow leaders blindly. Silently, drift away from civic life, and become disengaged and politically inactive.

I’m writing this piece to share a few lessons I’ve learnt and unlearnt throughout those past few years with the hope that some of them may guide and inspire practitioners interested to engage with our field: governance reform, institutional strengthening, and political development.

- Empathy – first and foremost, the people you’re working with may have seen their countries fail, experienced conflict, loss, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Is a traditional form of workshop or training delivered by someone from outside their country and context what they require at this time? Understand them, establish a human connection across boundaries that can outlive the project life cycle: this is what matters.

- Trust – Post-conflict contexts are saturated with international assistance. Those services are often poorly coordinated, with conflicting agendas, and competing demands. Unfortunately, some international organisations often work with limited understanding of the local context, political dynamics, and institutional realities and limitations. Your local partners will be pursued by several other major donors. It is crucial you establish trust and good-will at the outset of the project and ensure that your project is designed to help them do their jobs better, not burden them.

- Rapport – If you get the above right, then you’ll establish a strong rapport. People gravitate to those who understand them, listen to them, and with whom they enjoy working with – not people who prescribe solutions and impose their expertise.

- Impartiality – In those complicated, uncertain political environments in which deep divisions and polarisation often occur, development practitioners must maintain impartiality and engage with all partners on an equal footing to ensure solutions account for all needs and grievances and facilitate sustainable change.

- Political inclusion – During my work in Mosul, I conversed with officials in local government about the importance of political inclusion for all, including ethnic and religious minorities. Although they constituted the majority of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), women were significantly underrepresented and their priorities and demands were not addressed. We helped support the establishment of a Women in Peace and Security Committee composed of women politicians on a cross-party, cross-community basis, who were instrumental in addressing the grievances of women refugees by federal government and the donor community.

- Under promise and over deliver – The array of international development project management tools which you may or may not have heard of, such as LogFrames, Result Frameworks, and Theories of Change, are necessary for funders to evaluate the impact of their programmes, we all know reality tells a different story. In an extremely uncertain and challenging context, it is critical to stay adaptable to ensure programmes deliver the assistance partners require instead of simply what donors think is needed, and avoid the ‘tick-the-box’ approach.

- Maintaining momentum. At the inception phase of any project, ambitious plans are established, but setbacks are inevitable along the way. The test is to ensure momentum is maintained and the project provides support that is politically sensitive and contributes to local reform efforts, rather than one that overlaps or contradicts them.

- Locally-led reforms – No matter how sound, relevant, and practical the technical assistance is, if it does not become part of local reform efforts, it will not last.Projects must invest in creating a safe space where candid discussions can happen in confidence. This will enable politicians to collectively pinpoint the challenges with which they are grappling with and agree on what they can and cannot change.

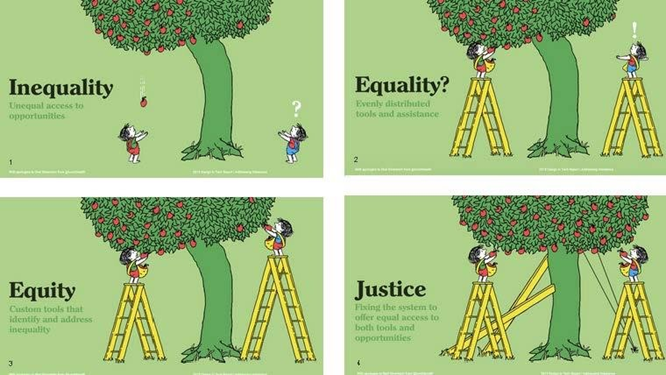

This field is not for the fainthearted. You’ll witness injustice, poverty, and lack of regard for basic human rights as normal features of ordinary life. Do not be disheartened. Inequalities are after all the result of corruption and misuse of power, and development support exists for this reason: to work on remedying those injustices. This is what development means to me.